Why Is Gerrymandering a Problem for the House of Representatives

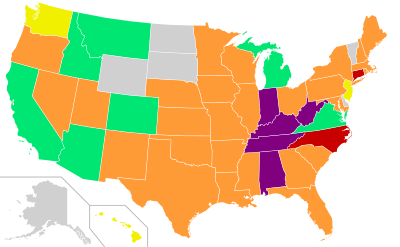

Partisan control of congressional redistricting afterwards the 2022 elections, with the number of U.S. House seats each state will receive.

Democratic command

Republican control

Split up or bipartisan control

Independent redistricting commission

No redistricting necessary

"The Gerry-mander" kickoff appeared in this cartoon-map in the Boston Gazette, March 26, 1812.

Gerrymandering in the United States has been used to increase the ability of a political party. Gerrymandering is the practice of setting boundaries of electoral districts to favor specific political interests within legislative bodies, often resulting in districts with convoluted, winding boundaries rather than compact areas. The term "gerrymandering" was coined after a review of Massachusetts's redistricting maps of 1812 set past Governor Elbridge Gerry noted that 1 of the districts looked similar a salamander.

In the U.s., redistricting takes place in each state about every 10 years, subsequently the decennial demography. Information technology defines geographical boundaries, with each district inside a country being geographically contiguous and having nigh the same number of state voters. The resulting map affects the elections of the country'southward members of the Us House of Representatives and the state legislative bodies. Redistricting has always been regarded equally a political exercise and in most states, it is controlled by state legislators and sometimes the governor (in some states the governor has no veto ability over redistricting legislation while in some states the veto override threshold is a unproblematic majority). When 1 political party controls the land'due south legislative bodies and governor'southward function, information technology is in a strong position to gerrymander district boundaries to reward its side and to disadvantage its political opponents.[1] Since 2010, detailed maps and loftier-speed calculating accept facilitated gerrymandering by political parties in the redistricting process, in lodge to proceeds control of state legislation and congressional representation and potentially to maintain that control over several decades, fifty-fifty against shifting political changes in a state's population. Gerrymandering has been sought[ description needed ] equally unconstitutional in many instances.

Typical gerrymandering cases in the United States have the form of partisan gerrymandering, which is aimed at favoring one political party while weakening some other; bipartisan gerrymandering, which is aimed at protecting incumbents by multiple political parties; and racial gerrymandering, which is aimed at weakening the power of minority voters.[ii]

Gerrymandering tin can also recreate districts with the aim of maximizing the number of racial minorities to aid particular nominees, who are minorities themselves. In another cases that have the same goal of diluting the minority vote, the districts are reconstructed in a way that packs minority voters into a smaller or limited number of districts.

In the 20th century and afterwards, federal courts accept accounted extreme cases of gerrymandering to be unconstitutional but have struggled with how to ascertain the types of gerrymandering and the standards that should be used to determine which redistricting maps are unconstitutional. The United states of america Supreme Court has affirmed in Miller v. Johnson (1995) that racial gerrymandering is a violation of constitutional rights and upheld decisions against redistricting that is purposely devised based on race. However, the Supreme Courtroom has struggled every bit to when partisan gerrymandering occurs (Vieth v. Jubelirer (2004) and Gill v. Whitford (2018)) and a landmark decision, Rucho v. Mutual Cause (2019), ultimately decided that questions of partisan gerrymandering represent a nonjusticiable political question, which cannot be dealt with by the federal court system. That decision leaves it to states and to Congress to develop remedies to challenge and to foreclose partisan gerrymandering. Some states have created contained redistricting commissions to reduce political drivers for redistricting. The research department of the nonpartisan nonprofit anti-corruption organization RepresentUs bug a Redistricting Report Card which rates the level of gerrymandered distortion of congressional district maps within each country,[3] [4] and its research suggests that broad swaths of the public "beyond partisan lines" are dissatisfied with gerrymandering and are ready for substantive reforms.[five]

Dissimilar ways to depict commune boundaries in a hypothetical country.

Partisan gerrymandering [edit]

Origins (1789–2000) [edit]

Printed in March 1812, this political cartoon was drawn in reaction to the newly fatigued Congressional electoral district of Due south Essex County fatigued by the Massachusetts legislature to favor the Democratic-Republican Party candidates of Governor Elbridge Gerry over the Federalists. The caricature satirizes the bizarre shape of a district in Essex County, Massachusetts, every bit a dragon-like "monster." Federalist newspapers' editors and others at the fourth dimension likened the district shape to a salamander, and the give-and-take gerrymander was built-in out of a portmanteau of that word and Governor Gerry'due south surname.

Partisan gerrymandering, which refers to redistricting that favors 1 political party, has a long tradition in the United states.

Starting from the William Cabell Rives in mid-19th century it is often stated that it precedes the 1789 election of the First U.S. Congress: namely, that while Patrick Henry and his Anti-Federalist allies were in control of the Virginia House of Delegates in 1788, they drew the boundaries of Virginia's 5th congressional district in an unsuccessful try to keep James Madison out of the U.S. House of Representatives.[6] Nonetheless, in early 20th century it was revealed that this theory was based on incorrect claims past Madison and his allies, and recent historical research disproved it altogether.[7]

The word gerrymander (originally written "Gerry-mander") was used for the first time in the Boston-Gazette (non to be dislocated with the Boston Gazette) on March 26, 1812, in reaction to a redrawing of Massachusetts state senate election districts nether the then-governor Elbridge Gerry (1744–1814), who signed a bill that redistricted Massachusetts to benefit his Democratic-Republican Political party. When mapped, one of the contorted districts to the due north of Boston was said to resemble the shape of a salamander.[8]

The coiner of the term "gerrymander" may never exist firmly established. Historians widely believe that the Federalist newspaper editors Nathan Hale, and Benjamin and John Russell were the instigators, but the historical record does not accept definitive evidence every bit to who created or uttered the discussion for the beginning time.[9] Appearing with the term, and helping to spread and sustain its popularity, was a political cartoon depicting a foreign animate being with claws, wings and a dragon-similar head satirizing the map of the odd-shaped district. This drawing was almost likely drawn by Elkanah Tisdale, an early 19th-century painter, designer, and engraver who was living in Boston at the time.[9] The give-and-take gerrymander was reprinted numerous times in Federalist newspapers in Massachusetts, New England, and nationwide during the remainder of 1812.

Gerrymandering soon began to exist used to describe not simply the original Massachusetts example, but besides other cases of district-shape manipulation for partisan gain in other states. The commencement known apply outside the firsthand Boston area came in the Newburyport Herald of Massachusetts on March 31, and the first known apply outside Massachusetts came in the Concord Gazette of New Hampshire on Apr 14, 1812. The first known use exterior New England came in the New York Gazette & General Advertiser on May xix. What may exist the first use of the term to depict the redistricting in another land (Maryland) occurred in the Federal Republican (Georgetown, Washington, DC) on Oct 12, 1812. There are at least 80 known citations of the discussion from March through December 1812 in American newspapers.[ix]

The do of gerrymandering the borders of new states continued past the Civil War and into the tardily 19th century. The Republican Political party used its control of Congress to secure the admission of more states in territories friendly to their party. A notable example is the admission of Dakota Territory as 2 states instead of i. By the rules for representation in the Electoral College, each new state carried at to the lowest degree three balloter votes, regardless of its population.

From time to fourth dimension, other names are given the "-mander" suffix to tie a particular effort to a item politician or group. These include "Jerrymander" (a reference to California Governor Jerry Chocolate-brown),[10] and "Perrymander" (a reference to Texas Governor Rick Perry).[11] [12]

In the 1960s, a series of "1 person, one vote" cases were decided by the Supreme Court, which resulted in a mandate of redistricting in response to the results of each census. Prior to these decisions, many states had stopped redrawing their districts. As a effect of the periodic need to redistrict, political conflicts over redistricting have sharply increased.[13]

2000–2010 [edit]

The potential to gerrymander a district map has been aided by advances in calculating power and capabilities. Using geographic data organisation and census data as input, mapmakers can apply computers to process through numerous potential map configurations to reach desired results, including partisan gerrymandering.[fourteen] Computers can appraise voter preferences and utilize that to "pack" or "cleft" votes into districts. Packing votes refers to concentrating voters in one voting district by redrawing congressional boundaries so that those in opposition of the party in charge of redistricting are placed into 1 larger district, therefore reducing the party's congressional representation. Cracking refers to diluting the voting power of opposition voters across many districts by redrawing congressional boundaries so that voting minority populations in each commune are reduced, therefore lowering the chance of a district-oriented congressional takeover. Both techniques atomic number 82 to what the Times describes as "wasted votes," which are votes that do not supply a party with any victory. These can either be a surplus of votes in ane commune for ane political party that are above the threshold needed to win, or any vote that has resulted in a loss.[15] A study done by the Academy of Delaware mentions situations in which an incumbent that is required to live in the commune they correspond can be "hijacked" or "kidnapped" into a neighboring district due to the redrawing of congressional boundaries, subsequently placing them in districts that are more difficult for them to win in.[xvi] Partisan gerrymandering often leads to benefits for a particular political political party, or, in some cases, a race.

In Pennsylvania, the Republican-dominated state legislature used gerrymandering to assistance defeat Democratic representative Frank Mascara. Mascara was elected to Congress in 1994. In 2002, the Republican Party altered the boundaries of his original commune and then much that he was pitted against swain Democratic candidate John Murtha in the election. The shape of Mascara's newly fatigued commune formed a finger that stopped at his street, encompassing his house, only not the spot where he parked his machine. Murtha won the election in the newly formed district.[17]

State legislatures take used gerrymandering forth racial or indigenous lines both to subtract and increment minority representation in state governments and congressional delegations. In the state of Ohio, a chat betwixt Republican officials was recorded that demonstrated that redistricting was being done to assist their political candidates. Furthermore, the discussions assessed race of voters as a factor in redistricting, considering African-Americans had backed Democratic candidates. Republicans obviously removed approximately 13,000 African-American voters from the district of Jim Raussen, a Republican candidate for the Business firm of Representatives, in an try to tip the scales in what was once a competitive district for Democratic candidates.[18]

International election observers from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Function for Autonomous Institutions and Human Rights, who were invited to discover and report on the 2004 national elections, expressed criticism of the U.S. congressional redistricting process and fabricated a recommendation that the procedures be reviewed to ensure genuine competitiveness of congressional ballot contests.[19]

2010–2020 [edit]

In the lead-up to the 2010 United States elections, the Republican Party initiated a plan called REDMAP, the Redistricting Majority Project, which recognized that the party in control of country legislatures would take the ability to prepare their congressional and legislative commune maps based on the pending 2010 Us Census in mode to assure that party'due south command over the side by side 10 years. The Republicans took significant gains from the 2010 elections across several states, and past 2011 and 2012, some of the new district maps showed Republican advantage through perceived partisan gerrymandering. This ready the stage for several legal challenges from voters and groups in the court system, including several heard at the Supreme Court level.[20]

In 2015, Thomas Hofeller was hired past the Washington Gratis Beacon to analyze what would happen if political maps were drawn based on the population of U.S. citizens of voting age rather than on the total population. He concluded that doing so "would be advantageous to Republicans and not-Hispanic whites." Although the report was not published, it was discovered later his death in 2018.[21] Attorney General William P. Barr and Commerce Secretary Wilbur L. Ross Jr. have refused to cooperate with an investigation into why the Trump administration added a U.S. citizenship question to the 2022 demography and specifically whether it seeks to benefit Republicans as suggested by Hofeller's study.[22]

Several land court rulings establish partisan gerrymandering to be impermissible under state constitutions, and several land election measures passed in 2022 that require non-partisan commissions for the 2022 redistricting bicycle.

Legality [edit]

U.Southward. congressional districts covering Travis Canton, Texas (outlined in red) in 2002, left, and 2004, right. In 2003, the majority of Republicans in the Texas legislature redistricted the land, diluting the voting power of the heavily Autonomous county by parceling its residents out to more Republican districts. In 2004 the orange district 25 was intended to elect a Democrat while the xanthous and pink commune 21 and district 10 were intended to elect Republicans. District 25 was redrawn as the issue of a 2006 Supreme Court determination. In the 2011 redistricting, Republicans divided Travis Canton between five districts, only one of which, extending to San Antonio, elects a Democrat.

2018 election results for the U.S. Firm of Representatives, showing Democratic Party vote share and seat share. While the overall vote share and seat share were the same at 54%, at that place were several states with significant differences in share. Annotation that several states with few or one representative announced at the 0 or 100% seat share. States with more representatives and sizable share differences are more than analytically relevant for evaluating the hazard of gerrymandering.[23]

Federal courts [edit]

Whether a redistricting results in a partisan gerrymandering has been a frequent question put to the United States court system, but which the courts accept generally avoided a potent ruling for fright of showing political bias towards either of the major parties.[24] The Supreme Court had ruled in Davis 5. Bandemer (1986) that partisan gerrymandering violates the Equal Protection Clause and is a justiciable matter. However, in its decision, the Court could non hold on the appropriate constitutional standard against which legal claims of partisan gerrymandering should be evaluated. Writing for a plurality of the Court, Justice White said that partisan gerrymandering occurred when a redistricting plan was enacted with both the intent and the outcome of discriminating against an identifiable political group. Justices Powell and Stevens said that partisan gerrymandering should be identified based on multiple factors, such as electoral commune shape and adherence to local government boundaries. Justices O'Connor, Burger, and Rehnquist disagreed with the view that partisan gerrymandering claims were justiciable and would take held that such claims should not be recognized past courts.[25] : 777–779 Lower courts institute it difficult to use Bandemer, and only in one subsequent case, Party of North Carolina v. Martin (1992),[26] did a lower court strike down a redistricting plan on partisan gerrymandering grounds.[25] : 783

The Supreme Court revisited the concept of partisan gerrymandering claims in Vieth v. Jubelirer (2004).[27] While the Courtroom upheld that partisan gerrymandering could be justiciable, the justices were divided in this specific instance as no clear standard against which to evaluate partisan gerrymandering claims emerged. Writing for a plurality, Justice Scalia said that partisan gerrymandering claims were nonjusticiable. A majority of the court would go on to allow partisan gerrymandering claims to be considered justiciable, but those justices had divergent views on how such claims should be evaluated.[28] Justice Anthony Kennedy, in a concurrence with the plurality, offered that a manageable means to determine when partisan gerrymandering occurred could be developed, and challenged lower courts to find such means.[25] : 819–821 The Court again upheld that partisan gerrymandering could be justiciable in League of United Latin American Citizens v. Perry (2006). While the specific case reached no determination of whether there was partisan gerrymandering, Justice John Paul Stevens'due south concurrence with the plurality added the notion of partisan symmetry, in that the balloter system should translate votes to representative seats with the same efficiency regardless of party.[29]

Opinions from Vieth and League, also as the strong Republican advantage created by its REDMAP plan, had led to a number of political scholars working aslope courts to develop such a method to determine if a district map was a justiciable partisan gerrymandering, equally to prepare for the 2022 elections. Many early attempts failed to proceeds traction the court organization, focusing more on trying to testify how restricting maps were intended to favor one party or disfavor the other, or that the redistricting eschewed traditional redistricting approaches.[29] Around 2014, Nicholas Stephanopoulos and Eric McGhee developed the "efficiency gap", a means to mensurate the number of wasted votes (votes either far in excess of what we necessary to secure a win for a party, or votes for a party that had petty chase to win) inside each district. The larger the gap of wasted votes between the two parties implied the more likely that the district maps supported a partisan gerrymandering, and with a sufficiently large gap it would exist possible to sustain that gap indefinitely. While not perfect, having several potential flaws when geography of urban centers were considered, the efficiency gap was considered to be the offset tool that met both Kennedy's and Stevens' suggestions.[30]

The first major legal test of the efficiency gap came into play for Gill v. Whitford (2016).[31] The District Court in the example used the efficiency gap statistic to evaluate the merits of partisan gerrymander in Wisconsin's legislative districts. In the 2012 election for the land legislature, the efficiency gap was xi.69% to 13% in favor of the Republicans. "Republicans in Wisconsin won 60 of the 99 Assembly seats, despite Democrats having a bulk of the statewide vote."[32]

Moving the Harris'south from a Democratic, Milwaukee commune into a larger Republican expanse was part of a strategy known as 'packing and cracking.' Heavily Democratic Milwaukee voters were 'packed' together in fewer districts, while other sections of Milwaukee were 'cracked' and added to several Republican districts ... diluting that Autonomous vote. The event? Three fewer Democrats in the state associates representing the Milwaukee area.

—PBS NewsHour October i, 2017

The disparity led to the federal lawsuit Gill 5. Whitford, in which plaintiffs declared that voting districts were gerrymandered unconstitutionally. The court found that the disparate treatment of Democratic and Republican voters violated the 1st and 14th amendments to the U.S. Constitution.[33] The District Courtroom'south ruling was challenged and appealed to the Supreme Courtroom of the U.s., which in June 2022 agreed to hear oral arguments in the example in the 2017–2018 term of court.The case was so dismissed due to lack of standing for the plaintiffs with no decision on the claim being fabricated. The example was then remanded for farther proceedings to demonstrate standing.[34] While previous redistricting cases before the Supreme Court take involved the Equal Protection examination, this case too centers on the applicability of the First Amendment freedom of association clause.[35] [36]

Benisek v. Lamone was a separate partisan gerrymandering case heard by the Supreme Court in the 2022 term, this over perceived Autonomous-favored redistricting of Maryland'south 6th congressional district, with plaintiffs trying to become a stay on the use of the new district maps prior to the October 2022 general ballot. The Court did not give opinions on whether the redistricting was unconstitutional, but did establish that on the basis of Gill that the instance should be reconsidered at the District Courtroom.[37] The District Court did subsequently rule the redistricting was unconstitutional, and that decision was appealed again to the Supreme Court and was heard under the proper name Lamone five. Benisek alongside Rucho v. Common Crusade on March 26, 2019.[38]

Yet another partisan redistricting case was heard past the Supreme Courtroom during the 2022 term. Rucho five. Common Cause deals with Republican-favored gerrymandering in Due north Carolina. The District Court had ruled the redistricting was unconstitutional prior to Gill; an initial challenge brought to the Supreme Courtroom resulted in an order for the District Court to re-evaluate their conclusion in light of Gill. The District Court, on rehearing, affirmed their previous decision. The state Republicans again sought for review past the Supreme Court which was heard aslope Lamone five. Benisek on March 26, 2019.[38]

Similarly, Michigan's post-2010 redistricting had been challenged, and in Apr 2019, a federal court determined the Republican-led redistricting to be an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander, and ordered the country to redraw districts in fourth dimension for the 2022 ballot.[39] [40] Within a week, a like conclusion was arrived past a federal district court reviewing Ohio's district maps since 2012 and were alleged unconstitutional as they were drawn by the Republican-majority lawmakers with "invidious partisan intent", and ordered the maps redrawn.[41] The Republican-favored maps led Ohio's residents to vote for a statewide initiative that requires the new redistricting maps after the 2022 Census to have at least fifty% blessing from the minority party.[42] The Republican political party sought an firsthand challenge to the redistricting order, and by tardily May 2019, the Supreme Court ordered both the courtroom-ordered redrawing to be put on hold until Republicans can prepare a complete petition, without commenting on the merits of the instance otherwise.[43] Additionally, observers to the Supreme Court recognized that the Court would be issuing its orders to the North Carolina and Maryland cases, which would likely affect how the Michigan and Ohio courtroom orders would be interpreted.[44]

Rucho v. Common Cause and Lamone v. Benisek were decided on June 27, 2019, which, in the 5–4 decision, adamant that judging partisan gerrymandering cases is outside of the remit of the federal court system due to the political questions involved. The majority opinion stated that farthermost partisan gerrymandering is still unconstitutional, simply it is up to Congress and state legislative bodies to discover ways to restrict that, such as through the use of independent redistricting commissions.[45] [46]

State courts [edit]

The Pennsylvania Supreme Courtroom ruled in League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania that gerrymandering was unconstitutional, ruling that the districts drawn to favor Republicans violated "free and equal" Elections Clause of the Pennsylvanian constitution and redrew the districts after the country government failed to comply with the borderline in its order to redraw.[47] The U.S. Supreme Court denied to hear the claiming and allowed the Pennsylvania Supreme Court maps to remain in place.[48]

In October 2019, a 3-gauge panel in Due north Carolina threw out a gerrymandered balloter map, citing violation of the constitution to disadvantage the Autonomous Political party.[49]

Bipartisan gerrymandering (favoring incumbents) [edit]

Bipartisan gerrymandering, where redistricting favors the incumbents in both the Autonomous and Republican parties, became especially relevant in the 2000 redistricting process, which created some of the nearly non-competitive redistricting plans in American history.[25] : 828 The Supreme Courtroom held in Gaffney five. Cummings (1973) that bipartisan gerrymanders are constitutionally permissible nether the Equal Protection Clause.[25] : 828 [50]

Racial gerrymandering [edit]

Racial makeup can be used as a means to create gerrymanders. There is overlap between racial and partisan gerrymandering, as minorities tend to favor Autonomous candidates; the N Carolina redistricting in Rucho five. Common Cause was such a case dealing with both partisan and racial gerrymanders. However, racial gerrymanders can also exist created without considerations of party lines.

Negative [edit]

"Negative racial gerrymandering" refers to a process in which district lines are drawn to prevent racial minorities from electing their preferred candidates.[51] : 26 Betwixt the Reconstruction Era and mid-20th century, white Southern Democrats effectively controlled redistricting throughout the Southern U.s.. In areas where some African-American and other minorities succeeded in registering, some states created districts that were gerrymandered to reduce the voting impact of minorities. Minorities were finer deprived of their franchise into the 1960s. With the passage of the Voting Rights Deed of 1965 and its subsequent amendments, redistricting to carve maps to intentionally diminish the power of voters who were in a racial or linguistic minority, was prohibited. The Voting Rights Deed was amended by Congress in the 1980s, Congress to "make states redraw maps if they take a discriminatory result."[15] In July, 2017, San Juan County, Utah was ordered to redraw its county commission and schoolhouse lath election districts once again after "U.Due south. District Judge Robert Shelby ruled that they were unconstitutional." It was argued that the phonation of Native Americans, who were in the majority, had been suppressed "when they are packed into gerrymandered districts."[52]

Affirmative [edit]

While the Equal Protection Clause, along with Section two and Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, prohibit jurisdictions from gerrymandering electoral districts to dilute the votes of racial groups, the Supreme Court has held that in some instances, the Equal Protection Clause prevents jurisdictions from cartoon district lines to favor racial groups. The Supreme Court starting time recognized these "affirmative racial gerrymandering" claims in Shaw 5. Reno (Shaw I) (1993),[53] holding that plaintiffs "may state a claim by alleging that [redistricting] legislation, though race neutral on its confront, rationally cannot be understood every bit anything other than an effort to separate voters into different districts on the ground of race, and that the separation lacks sufficient justification". The Supreme Court reasoned that these claims were cognizable because relying on race in redistricting "reinforces racial stereotypes and threatens to undermine our system of representative commonwealth by signaling to elected officials that they represent a particular racial group rather than their constituency as a whole".[53] : 649–650 [54] : 620 Subsequently opinions characterized the blazon of unconstitutional damage created by racial gerrymandering as an "expressive harm",[25] : 862 which police force professors Richard Pildes and Richard Neimi accept described as a damage "that results from the thought or attitudes expressed through a governmental action."[55]

Subsequent cases further defined the counters of racial gerrymandering claims and how those claims relate to the Voting Rights Human activity. In Us 5. Hays (1995),[56] the Supreme Court held that only those persons who reside in a challenged district may bring a racial gerrymandering claim.[54] : 623 [56] : 743–744 In Miller v. Johnson (1995),[57] the Supreme Court held that a redistricting plan must be subjected to strict scrutiny if the jurisdiction used race equally the "predominant factor" in determining how to draw district lines. The court defined "predominance" every bit meaning that the jurisdiction gave more priority to racial considerations than to traditional redistricting principles such every bit "compactness, contiguity, [and] respect for political subdivisions or communities divers by actual shared interests."[54] : 621 [57] : 916 In determining whether racial considerations predominated over traditional redistricting principles, courts may consider both direct and circumstantial evidence of the jurisdiction's intent in drawing the district lines, and irregularly-shaped districts establish strong coexisting evidence that the jurisdiction relied predominately on race.[25] : 869 If a court concludes that racial considerations predominated, then a redistricting plan is considered a "racially gerrymandered" plan and must be subjected to strict scrutiny, meaning that the redistricting program will be upheld as constitutional merely if it is narrowly tailored to advance a compelling state interest. In Bush five. Vera (1996),[58] : 983 the Supreme Courtroom in a plurality opinion causeless that compliance with Section two or Department v of the Act constituted compelling interests, and lower courts have treated these two interests every bit the only compelling interests that may justify the creation of racially gerrymandered districts.[25] : 877

In Hunt v. Cromartie (1999) and its follow-up case Easley five. Cromartie (2001), the Supreme Court canonical a racially focused gerrymandering of a congressional district on the grounds that the definition was not pure racial gerrymandering just instead partisan gerrymandering, which is constitutionally permissible. With the increasing racial polarization of parties in the South in the U.S. every bit bourgeois whites motility from the Democratic to the Republican Political party, gerrymandering may become partisan and also attain goals for indigenous representation.

Various examples of affirmative racial gerrymandering have emerged. When the state legislature considered representation for Arizona's Native American reservations, they thought each needed their own House fellow member, because of historic conflicts between the Hopi and Navajo nations. Since the Hopi reservation is completely surrounded by the Navajo reservation, the legislature created an unusual district configuration for the 2d congressional district that featured a fine filament along a river course several hundred miles in length to attach the Hopi reservation to the rest of the district; the arrangement lasted until 2013. The California state legislature created a congressional commune (2003–2013) that extended over a narrow littoral strip for several miles. It ensured that a common community of interest volition be represented, rather than having portions of the coastal areas be split up into districts extending into the interior, with domination past inland concerns.

In the example of League of United Latin American Citizens five. Perry, the United States Supreme Courtroom upheld on June 28, 2006, most of a Texas congressional map suggested in 2003 by one-time United States House Majority Leader Tom Delay, and enacted by the state of Texas.[59] The 7–two decision allows state legislatures to redraw and gerrymander districts every bit often as they similar (not just later on the decennial census). In his dissenting opinion in LULAC 5. Perry, Justice John Paul Stevens, joined by Justice Stephen Breyer, quoted Bill Ratliffe, former Texas lieutenant governor and member of the Texas land senate saying, "political proceeds for the Republicans was 110% the motivation for the plan," and argued that a plan whose "sole intent" was partisan could violate the Equal Protection Clause.[60] This was notable as previously Justice Stevens had joined Justice Breyer'due south opinion in Easley v. Cromartie, which held that explicitly partisan motivation for gerrymanders was permissible and a defence force against claims of racial gerrymandering. Thus they may work to protect their political parties' standing and number of seats, so long as they do not harm racial and ethnic minority groups. A 5–4 majority declared i congressional district unconstitutional in the case considering of harm to an ethnic minority.

Inclusion of prisons [edit]

Since the 1790 United States Demography, the United states of america Demography Agency has counted prisoner populations as residents of the districts in which they are incarcerated, rather than in the same district equally their previous pre-incarceration residence. In jurisdictions where incarcerated people cannot vote, moving boundaries around a prison tin can create a district out of what would otherwise be a population of voters which is too small. I farthermost example is Waupun, Wisconsin, where two city council districts are made up of 61% and 76% incarcerated people, simply as of 2019, neither elected representative has visited the local prisons.[61]

"Prison gerrymandering" has been criticized for distorting racial demographics and, every bit a upshot, political representation.[62] A 2022 article in The New York Times argued that, equally prisoners are unduly people of color from urban areas incarcerated in rural areas, "counting people where they're imprisoned takes political ability away from racial minorities in cities and transfers information technology to whites in rural areas."[63]

Reform efforts [edit]

In 2018, the Census Bureau announced that information technology would retain the policy, asserting that the policy "is consequent with the concept of usual residence, equally established by the Census Act of 1790," but besides conceding assist to states who wish "'to 'move' their prisoner population dorsum to the prisoners' pre-incarceration addresses for redistricting and other purposes".[64]

A number of states accept since ordered their state governments to recognize incarcerated persons equally residents of their pre-incarceration homes for the sake of legislative and congressional redistricting at all levels. These include us of Maryland and New York in fourth dimension for the 2010 Census. States that made similar orders in time for the 2022 Demography include California (2011), Delaware (2010), Nevada (2019), Washington (2019), New Jersey (2020), Colorado (2020),[65] Virginia (2020) and Connecticut (2021)

Additionally, Colorado (2002), Michigan (1966), Tennessee (2016) and Virginia (2013) accept passed laws restricting counties and municipalities from (or allowing counties and municipalities to avert) prison-based redistricting, and Massachusetts passed a 2022 resolution requesting the Census Bureau to end the exercise of counting prisoners in their incarceration districts.

Remedies [edit]

Various political and legal remedies have been used or proposed to diminish or foreclose gerrymandering in the land.[25]

Neutral redistricting criteria [edit]

Various ramble and statutory provisions may hogtie a court to strike down a gerrymandered redistricting programme. At the federal level, the Supreme Court has held that if a jurisdiction'due south redistricting plan violates the Equal Protection Clause or Voting Rights Act of 1965, a federal court must order the jurisdiction to propose a new redistricting plan that remedies the gerrymandering. If the jurisdiction fails to propose a new redistricting plan, or its proposed redistricting plan continues to violate the police, then the court itself must draw a redistricting plan that cures the violation and employ its equitable powers to impose the plan on the jurisdiction.[25] : 1058 [66] : 540

In the Supreme Court case of Karcher v. Daggett (1983),[67] a New Jersey redistricting programme was overturned when it was constitute to be unconstitutional by violating the constitutional principle of 1 person, one vote. Despite the state claiming its unequal redistricting was done to preserve minority voting power, the courtroom plant no show to support this and deemed the redistricting unconstitutional.[68]

At the state level, state courts may social club or impose redistricting plans on jurisdictions where redistricting legislation prohibits gerrymandering. For example, in 2010 Florida adopted ii country constitutional amendments that prohibit the Florida Legislature from drawing redistricting plans that favor or disfavor whatever political party or incumbent.[69] Ohio residents passed an initiative in 2022 that requires the redistricting maps to have at least 50% blessing by the minority party in the legislature.[42]

Moon Duchin, a Tufts University professor, has proposed the use of metric geometry to measure out gerrymandering for forensic purposes.[seventy]

Redistricting commissions [edit]

Congressional redistricting methods by state after the 2022 census:

Contained commission

Politician committee

Passed by legislature with gubernatorial approving

Passed by legislature, governor plays no role

Passed by legislature, simple majority veto override

Not applicable due to having one at-large district

* The Ohio Constitution requires that redistricting votes in the Ohio Legislature exist bipartisan, with a minimum number of votes required from both parties for a redistricting human activity to pass

Congressional redistricting methods by country after the 2010 census:

State legislatures control redistricting

Commissions control redistricting

Nonpartisan staff develop the maps, which are then voted on by the state legislature

No redistricting due to having only 1 congressional district

Some states have established non-partisan redistricting commissions with redistricting authority. Washington,[71] Arizona,[72] and California have created standing committees for redistricting following the 2010 demography. However, it has been argued that the Californian continuing commission has failed to end gerrymandering.[73] Rhode Island[74] and the New Jersey Redistricting Commission have developed advert hoc committees, but developed the by ii decennial reapportionments tied to new census data.

The Arizona State Legislature challenged the constitutionality of a non-partisan committee, rather than the legislature, for redistricting. In Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Contained Redistricting Committee (2015), the United States Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of non-partisan commissions.[75]

Alternative voting systems [edit]

The predominant voting system in the Usa is a kickoff-past-the-postal service system that uses single-fellow member districts. Diverse alternative district-based voting systems that exercise not rely on redistricting, or rely on redistricting minimally, have been proposed that may mitigate against the ability to gerrymander. These systems typically involve a grade of at-large elections or multimember districts. Examples of such systems include the single-transferable vote, cumulative voting, and limited voting.[76]

Proportional voting systems, such every bit those used in all but three European states,[77] would bypass the problem altogether. In these systems, the political party that gets, for example, 30 per centum of the votes gets roughly 30 per centum of the seats in the legislature. Although it is mutual for European states to have more than than ii parties, a sufficiently loftier election threshold can limit the number of parties elected. Some proportional voting systems have no districts or larger multimember districts and may interruption the potent constituency link, a cornerstone of electric current American politics, past eliminating the dependency of individual representatives on a concrete electorate.[78] All the same, systems like mixed-member proportional representation keep local single-member constituencies but balance their results with nationally elected or regionally-elected representatives to accomplish political party proportionality.

Effects [edit]

Republic [edit]

A 2022 written report plant that gerrymandering "impedes numerous political party functions at both the congressional and country firm levels. Candidates are less likely to contest districts when their party is disadvantaged by a districting plan. Candidates that do choose to run are more than likely to have weak resumes. Donors are less willing to contribute money. And ordinary voters are less apt to support the targeted political party. These results suggest that gerrymandering has long‐term furnishings on the wellness of the autonomous process beyond simply costing or gaining parties seats in the legislature."[79]

Gerrymandering and the environs [edit]

Gerrymandering has the ability to create numerous problems for the constituents impacted by the redistricting. A written report done by the peer-reviewed Environmental Justice Journal analyzed how gerrymandering contributes to environmental racism. It suggested that partisan gerrymandering tin can often lead to adverse health complications for minority populations that live closer to Usa superfund sites and additionally found that during redistricting periods, minority populations are "effectively gerrymandered out" of districts that tend to accept fewer people of colour in them and are farther away from toxic waste material sites. This redistricting can be seen every bit a deliberate motion to farther marginalize minority populations and restrict them from gaining access to congressional representation and potentially fixing ecology hazards in their communities.[lxxx]

Gerrymandering and the 2022 midterm elections [edit]

Gerrymandering was considered by many Democrats to be 1 of the biggest obstacles they came across during the 2022 U.S. midterm election. In early 2018, both the United States Supreme Court and the Pennsylvania Supreme Court determined that the Republican parties in North Carolina and Pennsylvania had committed unconstitutional gerrymandering in the respective cases Cooper v. Harris and League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania v. Democracy of Pennsylvania. In the case of Pennsylvania, the map was reconfigured into an evenly split up congressional delegation, which gave Democrats in Pennsylvania more congressional representation and later on aided the Democrats in flipping the U.Southward. Business firm of Representatives. In dissimilarity, North Carolina did not reconfigure the districts prior to the midterm elections, which ultimately gave Republicans in that location an border during the election. Republicans in North Carolina caused 50% of the vote, which subsequently garnered them about 77% of the available seats in congress.[81] [82]

| Country | % Vote D | % Vote R | % Seats D | % Seats R | Total Seats | Deviation Between D | Deviation Between R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Carolina | 48.35% | l.39% | 23.08% | 76.92% | thirteen | −25.27% | 26.53% |

| Ohio | 47.27% | 52% | 25% | 75% | 16 | −22.27% | 23% |

Other factors affecting redistricting [edit]

At a federal level, gerrymandering has been blamed for a subtract in competitive elections, move toward farthermost party positions, and gridlock in Congress. Harry Enten of FiveThirtyEight argues that decreasing contest is partly due to gerrymandering, but even more than so due to the population of the United states of america cocky-segregating past political credo, which is seen in by-county voter registrations. Enten points to studies which find that factors other than gerrymandering account for over 75% of the increment in polarization in the past forty years, presumably due largely to changes among voters themselves. Because the Senate (which cannot be gerrymandered due to the stock-still country borders) has been passing fewer bills but the Business firm (which is subject to gerrymandering) has been passing more than (comparing 1993–2002 to 2013–2016), Enten concludes gridlock is due to factors other than gerrymandering.[83]

Examples of gerrymandered U.S. districts [edit]

| North Carolina's twelfth congressional district between 2003 and 2022 was an example of packing. The district has predominantly African-American residents who vote for Democrats.[84] |

| California's 23rd congressional district was an case of packing confined to a narrow strip of coast drawn from iii large counties. The district shown was radically redrawn by California's not-partisan commission after the 2010 census. | |

| California'due south 11th congressional district featured long, strained projections and counter-projections of other districts, achieving mild only reliable packing. The district comprised a selection of people and communities favorable to the Republican Party. It was redrawn from the version shown later on the 2010 demography. |

| Bi-partisan incumbent gerrymandering produced California'south 38th congressional district, home to Grace Napolitano, a Democrat, who ran unopposed in 2004. This district was redrawn by California's non-partisan commission after the 2010 census. |

| Texas'due south controversial 2003 partisan gerrymander produced Texas District 22 for former Rep. Tom Filibuster, a Republican. A packed seat of Republicans based on by results of its many voting districts, it features 2 necks and a counter-projection. |

| The odd shapes — distended projections and not-natural feature-based wiggly boundaries — of California Senate districts in southern California (2008) have led to complaints of gerrymandering. |

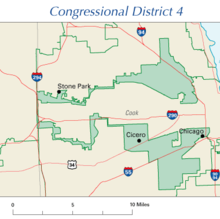

| Illinois'due south 4th congressional district has the moniker "the earmuffs" and amounts to packing of ii mainly Hispanic areas.[85] It has had in relative terms hairline contiguity along Interstate 294 and two necks at right angles, forming a very long neck between two areas, which was somewhat widened in 2013.[86] |

| Afterward the Democrat Jim Matheson was elected in 2000, the Utah legislature redrew the 2nd congressional district to favor hereafter Republican majorities. The predominantly Democratic city of Salt Lake City was connected to predominantly Republican eastern and southern Utah through a thin sliver of state running through Utah County. Nevertheless, Matheson continued to be re-elected. In 2011, the legislature created new congressional districts that combined conservative rural areas with more urban areas to dilute Democratic votes. |

| Illinois'south 17th congressional district in the western portion of the land was gerrymandered: the major urban centers are anchored and Decatur is included, although nearly isolated from the primary commune. It was redrawn in 2013. |

| Maryland's 3rd congressional district was listed in the superlative ten of the most gerrymandered districts in the United states by The Washington Post in 2014.[87] The district is drawn to favor Democratic candidates. Current MD-three representative John Sarbanes has put forth the For the People Act of 2022 aimed at U.S. electoral reform to accost partisan gerrymandering, voting rights and other issues.[88] [89] |

| North Carolina's 4th congressional district encompassed parts of Raleigh, Hillsborough, and the entirety of Chapel Loma. The commune was considered to be 1 of the nearly gerrymandered districts in N Carolina and the Us as a whole.[87] The district was redrawn in 2017. |

See too [edit]

- California redistricting propositions

- Proposition 11 (2008)

- Proposition 20 (2010)

- Electoral geography

- Checkerboarding (land)

- Gerrymandering (movie)

- Kilgarlin v. Martin

- Voter suppression

- United States congressional apportionment

- For the People Human activity of 2019

- Katie Fahey

- Thomas Hofeller

- Democratic recidivism

- RepresentUs

References [edit]

- ^ Here are the nearly obscenely gerrymandered congressional districts in America

- ^ "How racial gerrymandering deprives blackness people of political power". The Washington Post . Retrieved Dec 13, 2018.

- ^ Katerina Barton (producer) Melissa Harris-Perry (host) (November 12, 2021). "Redistricting and Voting Rights". WNYC Studios. Retrieved Jan 21, 2022.

...A collaboration between the Princeton Electoral Innovation Lab and RepresentUS started handing out Redistricting Written report Cards to keep a bank check on bad actors as they depict new political maps:...

- ^ SIMONE CARTER (Apr 23, 2021). "This is Some Dark Orwellian Sh*t': Actor Ed Helms Discovers Gerrymandering in New Ad". Dallas Observer. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

...The short picture show is the latest button to tackle gerrymandering past the star-studded anti-abuse organization RepresentUs. In addition to Helms, who serves on the lath of directors, Hollywood royalty Jennifer Lawrence, Michael Douglas and Spike Jonze are members of the group's "cultural council."... .

- ^ Julia Hotz (April 28, 2021). "Can "democracy dollars" keep real dollars out of politics? Seattle gave residents $100 in a bid to make the city's campaign contributions more than representative of its electorate. Now, the programme is spreading". Applied science Review. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

...Jack Noland, research manager at RepresentUs, ... "Across partisan lines ... there's this feeling that the arrangement isn't working equally intended and that regular people"...

- ^ Labunski, Richard. James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights, New York: Oxford University Printing, 2006

- ^ Hunter, Thomas Rogers (2011). "The First Gerrymander?: Patrick Henry, James Madison, James Monroe, and Virginia's 1788 Congressional Districting". Early American Studies. 9 (3): 781–820. doi:10.1353/eam.2011.0023. S2CID 143700791.

- ^ Griffith, Elmer (1907). The Rise and Development of the Gerrymander. Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Co. pp. 72–73. OCLC 45790508.

- ^ a b c Martis, Kenneth C. (2008). "The Original Gerrymander". Political Geography. 27 (iv): 833–839. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2008.09.003.

- ^ Thomas B. Hofeller, "The Looming Redistricting Reform; How volition the Republican Party Fare?", Politico, 2011.

- ^ Wasserman, David (August 19, 2011). "'Perrymander': Redistricting Map That Rick Perry Signed Has Texas Hispanics Up in Artillery". National Journal. Archived from the original on January sixteen, 2012.

- ^ Gersh, Marker (September 21, 2011). "Redistricting Journal: Showdown in Texas—reasons and implications for the Business firm, and Hispanic vote". CBS News. Archived from the original on September 22, 2011. Retrieved May fourteen, 2012.

- ^ McGhee, Eric (2020). "Partisan Gerrymandering and Political Science". Annual Review of Political Science. 23: 171–185. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-060118-045351.

- ^ Ellenburg, Jordan (October 6, 2017). "How Computers Turned Gerrymandering Into a Science". The New York Times . Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ a b Bazelon, Emily (August 29, 2017). "The New Front end in the Gerrymandering Wars: Commonwealth vs. Math". The New York Times . Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ Mackenzie, John (August 29, 2017). "Gerrymandering and Legislator Efficiency" (PDF). University of Delaware. Archived from the original (PDF) on January eleven, 2019. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- ^ Thomas Lloyd Brunell (2008). Redistricting and Representation: Why Competitive Elections Are Bad for America. Psychology Press. p. 69. ISBN9780415964524 . Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ^ "Republican Party Politics (Part Two)". WCPO. April 29, 2002. Archived from the original on May 20, 2002.

- ^ "XI" (PDF) . Retrieved August 5, 2009.

- ^ Newkirk II, Vann (October 28, 2017). "How Redistricting Became a Technological Arms Race". The Atlantic . Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ Wines, Michael (May 30, 2019). "Deceased Thou.O.P. Strategist's Hard Drives Reveal New Details on the Census Citizenship Question". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- ^ Davis, Julie Hirschfeld; Savage, Charlie (June 12, 2019). "Trump Asserts Executive Privilege on 2022 Census Documents". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- ^ Wasserman, Dave; Flinn, Ally. "2018 House Pop Vote Tracker". Cook Political Study. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- ^ Graham, David (January 23, 2018). "Has the Tide Turned Against Partisan Gerrymandering?". The Atlantic . Retrieved Apr 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Issacharoff, Samuel; Karlan, Pamela S.; Pildes, Richard H. (2012). The Constabulary of Commonwealth: Legal Structure of the Political Process (4th ed.). Foundation Press. ISBN978-1-59941-935-0.

- ^ Party of Northward Carolina v. Martin, 980 F.2d 943 (fourth Cir. 1992)

- ^ Vieth 5. Jubelirer, 541 U.S. 267 (2004)

- ^ Engstrom, Richard. 2006. "Reapportionment." Federalism in America: An Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b Stephanopoulos, Nicholas (July 2, 2014). "Hither'south How We Can End Gerrymandering Once and for All". The New Republic . Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ Kean, Sam (January 26, 2018). "The Flaw in America's 'Holy Grail' Against Gerrymandering". The Atlantic . Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ Whitford v Gill decision

- ^ Weber, Sam; Fong, Laura (October 1, 2017). "Supreme Court to hear case testing the limits of partisan gerrymandering". PBS NewsHour . Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ Wines, Michael (November 21, 2016). "Judges Find Wisconsin Redistricting Unfairly Favored Republicans". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Liptak, Adam (June 19, 2017). "Justices to Hear Major Challenge to Partisan Gerrymandering". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 19, 2017. Retrieved Feb 25, 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Grofman, Bernard (January 31, 2017). "The Supreme Court volition examine partisan gerrymandering in 2017. That could change the voting map". The Washington Post . Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ Prokop, Andrew (June 18, 2018). "The Supreme Courtroom even so won't crack down on partisan gerrymandering — nonetheless, at to the lowest degree". Vox . Retrieved Dec 19, 2018.

- ^ de Vogue, Ariane (June 18, 2018). "Supreme Court sidesteps partisan gerrymandering cases, allow maps stand for at present". CNN . Retrieved June eighteen, 2018.

- ^ a b "Docket for xviii-726". www.supremecourt.gov . Retrieved February eleven, 2022.

- ^ League of Women Voters of Michigan et al v. Johnson opinion and order

- ^ Wines, Michael (April 25, 2019). "Judges Rule Michigan Congressional Districts Are Unconstitutionally Gerrymandered". The New York Times . Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "OPINION AND Lodge for League of Women Voters of Michigan et al v. Johnson :". Justia Dockets & Filings . Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Gabriel, Trip; Wines, Michael (May iii, 2019). "Ohio Congressional Map Is Illegal Gerrymander, Federal Courtroom Rules". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 20, 2020. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ "Docket for 18A1171". world wide web.supremecourt.gov . Retrieved February eleven, 2022.

- ^ Grogorian, Deborah (May 24, 2019). "Supreme Courtroom temporarily blocks rulings requiring new voting maps for Ohio and Michigan". NBC News . Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (June 27, 2019). "Supreme Court Says Constitution Does Not Bar Partisan Gerrymandering". The New York Times . Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ^ "US supreme court declines to block partisan gerrymandering". TheGuardian.com. June 27, 2019.

- ^ Bycoffe, Aaron (February 20, 2018). "Pennsylvania'due south New Map Helps Democrats. But It'southward Not A Autonomous Gerrymander". Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (March nineteen, 2018). "Supreme Court Won't Block New Pennsylvania Voting Maps". The New York Times . Retrieved May half dozen, 2019.

- ^ Wines, Michael; Fausset, Richard (September three, 2019). "North Carolina's Legislative Maps Are Thrown Out past State Court Panel". The New York Times.

- ^ Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.South. 735 (1973)

- ^ Whitby, Kenny J. (December 21, 2000). The Color of Representation: Congressional Beliefs and Blackness Interests. Academy of Michigan Press. ISBN978-0472087020.

- ^ Toll, Michelle Fifty. (July 20, 2017). "United states Estimate: Utah canton election maps must be redrawn again". Metro News. Salt Lake City.

- ^ a b Shaw five. Reno (Shaw I), 509 U.Due south. 630 (1993)

- ^ a b c Ebaugh, Nelson (1997). "Refining the Racial Gerrymandering Claim: Bush v. Vera". Tulsa Law Journal. 33 (two). Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- ^ Pildes, Richard; Niemi, Richard (1993). "Expressive Harms, "Baroque Districts," and Voting Rights: Evaluation Election-District Appearances subsequently Shaw five. Reno". Michigan Law Review. 92 (three): 483–587. doi:10.2307/1289795. JSTOR 1289795.

- ^ a b United States 5. Hays, 515 U.S. 737 (U.S. 1995)

- ^ a b Miller 5. Johnson, 515 U.Due south. 900 (1995).

- ^ Bush-league v. Vera 517 U.S. 952 (1996).

- ^ "Loftier courtroom upholds most of Texas redistricting map". CNN. Associated Press. June 28, 2006.

- ^ Calidas, Douglass (2008). "Hindsight Is twenty/20: Revisiting the Reapportionment Cases to Gain Perspective on Partisan Gerrymanders". Duke Law Journal. 57 (five): 1413–1447. JSTOR 40040622.

- ^ Hansi Lo Wang Facebook Twitter Kumari and Kumari Devarajan (December 31, 2019). "'Your Body Being Used': Where Prisoners Who Tin can't Vote Fill Voting Districts". NPR. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ "When Your Body Counts But Your Vote Does Not: How Prison Gerrymandering Distorts Political Representation". Time . Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ The Editorial Lath (April xi, 2021). "Stance | You've Heard About Gerrymandering. What Happens When It Involves Prisons?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ The states Demography Agency (February 8, 2018). "Final 2022 Census Residence Criteria and Residence Situations". Federal Register. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved Jan 12, 2021.

- ^ Singer, Daliah (April 14, 2020). "Colorado Is the Eighth State To End Prison-Based Gerrymandering". 5280. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved April twenty, 2020.

- ^ Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535(1978)

- ^ Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725 (1983)

- ^ "Karcher v. Daggett – 462 U.Southward. 725 (1983)". Justia: US Supreme Court Middle.

- ^ "Election 2010: Palm Embankment Canton & Florida Voting, Candidates, Endorsements | The Palm Beach Post". Projects.palmbeachpost.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2010. Retrieved Dec 19, 2010.

- ^ Najmabadi, Shannon (February 22, 2017). "Meet the Math Professor Who's Fighting Gerrymandering With Geometry". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on Nov 25, 2020. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ Washington Land Redistricting Commission "Washington State Redistricting Committee". Redistricting.wa.gov. Retrieved Baronial v, 2009.

- ^ Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission "Arizona Independent Redistricting Committee". Azredistricting.org. Retrieved August five, 2009.

- ^ "How Democrats Fooled California'due south Redistricting Commission". December 22, 2011.

- ^ Rhode Island Reapportionment Committee Archived October xviii, 2007.

- ^ 576 U.S. ___, June 2022 (link to slip opinion), retrieved 2015-07-05.

- ^ See more often than not Mulroy, Steven J. (1998). "The Way Out: A Legal Standard for Imposing Alternative Electoral Systems as Voting Rights Remedies". Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Police Review. 33. SSRN 1907880.

- ^ "Which European countries use proportional representation?". www.electoral-reform.org.uk Balloter Reform Society. December 2018.

- ^ "Advantages and disadvantages of List PR". www.aceproject.org ACE Projection.

- ^ Stephanopoulos, Nicholas O.; Warshaw, Christopher (2020). "The Bear on of Partisan Gerrymandering on Political Parties". Legislative Studies Quarterly. 45 (iv): 609–643. doi:10.1111/lsq.12276. ISSN 1939-9162. S2CID 213781705.

- ^ Kramar, David (Feb 1, 2018). "A Spatially Informed Analysis of Environmental Justice: Analyzing the Effects of Gerrymandering and the Proximity of Minority Populations to U.S. Superfund Sites". Environmental Justice Periodical. doi:10.1089/env.2017.0031.

- ^ Lieb, David (November 17, 2018). "Midterm Elections Show How Gerrymandering is Difficult to Overcome". U.S. News & World Study. Archived from the original on November 20, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2018.

- ^ Ingraham, Christopher (November 9, 2018). "One state stock-still its gerrymandered districts, the other didn't. Here's how the election played out in both". The Washington Mail service . Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ Enten, Harry (Jan 26, 2018). "Ending Gerrymandering Won't Fix What Ails America". FiveThirtyEight . Retrieved Dec 2, 2018.

- ^ Blau, Max (October 19, 2016). "Drawing the line on the most gerrymandered district in America". The Guardian . Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ^ Blake, Aaron (July 27, 2011). "Name that district! (Gerrymandering edition)". Washington Post . Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- ^ "How to rig an election". The Economist. April 25, 2002.

- ^ a b Ingraham, Christopher (May fifteen, 2014). "America's nearly gerrymandered congressional districts". Washington Postal service. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ Sarbanes, John (January 3, 2019). "H.R.one – 116th Congress (2019–2020): To expand Americans' admission to the ballot box, reduce the influence of big money in politics, and strengthen ethics rules for public servants, and for other purposes". www.congress.gov. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved January vi, 2019.

- ^ 116th Congress (2019) (January 3, 2019). "H.R. 1 (116th)". Legislation. GovTrack.u.s.a.. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

For the People Deed of 2019

Further reading [edit]

- Daley, David (2016). Ratf**ked: Why Your Vote Doesn't Count. Liveright. ISBN978-1631491627.

- Daley, David (2020). Unrigged: How Americans Are Battling Back to Salvage Democracy. Liveright. ISBN978-1631495755.

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Gerrymandering in the United states of america at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gerrymandering in the United states of america at Wikimedia Commons

General [edit]

- Polk, James. "Why your vote for Congress might not matter." CNN. Friday November xviii, 2011.

- Understanding Congressional Gerrymandering: 'Information technology's Moneyball Applied To Politics'. Interview with Ratf**ked author David Daley. NPR, June fifteen, 2016.

- This is actually what America would await similar without gerrymandering, Washington Mail service

- Dickson v. Rucho – SCOTUSBlog profile; Brennan Center for Justice profile – Due north Carolina redistricting litigation

- Gerrymandering: Why Your Vote Doesn't Count, an article from Mother Jones Magazine

- The Gerrymandering Projection – FiveThirtyEight

Simulations [edit]

- Gerryminder – An online redistricting simulation.

- Redistricting The Nation uses GIS and web technology to interactively explore redistricting

- The Redistricting Game – Where Practise You Draw the Lines – a simulation of how redistricting works, developed past USC Game Innovation Lab of the USC School of Cinematic Arts Interactive Media Division.

- The Atlas Of Redistricting – maps drawn by various critera

- Impartial Automated Redistricting – maps optimized for compactness and equal population merely, based on 2010 census

- Splitline districtings of all 50 states + DC + PR

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerrymandering_in_the_United_States#:~:text=Gerrymandering%20in%20the%20United%20States%20has%20been%20used%20to,power%20of%20a%20political%20party.&text=When%20one%20party%20controls%20the,to%20disadvantage%20its%20political%20opponents.

0 Response to "Why Is Gerrymandering a Problem for the House of Representatives"

ارسال یک نظر